Luckily, he doesn’t know what I was doing while away.

Luckily, he doesn’t know what I was doing while away.

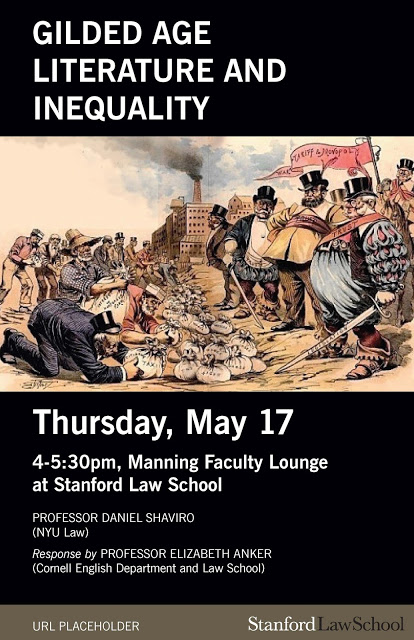

First, on Thursday, May 17, at 4 pm, I’ll be giving a talk entitled “Gilded Age Literature and Inequality.” This relates to my literature book project – now in two parts, with Book 1 to be entitled Dangerous Grandiosity: Literary Perspectives on High-End Inequality Through the First Gilded Age.

I’ll be speaking for up to 40 minutes, and have more or less written up a talk that I may post afterwards on SSRN and/or here. In addition to discussing the project in general, it focuses in particular on my chapter discussing E.M. Forster’s Howards End. Elizabeth Anker of Cornell (both the law school and the English Department) will be the respondent, and then there will be Q and A.

There doesn’t seem to be a link posted yet for this event, but I will provide it here once available.

Then, on May 18-19, there will be a Law and Humanities Conference at Stanford, hosted by Bernadette Meyler of Stanford (who also kindly arranged my literature book event) and Simon Stern of Toronto.

As per the conference program, I’ll be participating, including as the respondent at a May 19 panel entitled “Areas of Substantive Law” that will feature papers by Daniel Williams of Harvard, Andrew Gilden of Williamette, and Sherally Munshi of Georgetown.

I’m looking forward to these events, which I anticipate will be welcomedly (to coin a new word) horizon-expanding.

The current draft was written before the 2017 tax act took form, but the act then added greatly to its immediate policy relevance (as will no doubt be reflected in the next draft). In particular, it’s directly relevant to the question of whether one of the key international provisions in the 2017 act, known as GILTI (for “global intangible low-taxed income”) is compatible with bilateral tax treaties. This is not just a U.S. question under U.S. tax treaties, although it certainly is that, since, if other countries choose to enact GILTI-like rules they would face the same question under other treaties.

In broad outline, GILTI works as follows. (And again, I have a forthcoming article draft that discusses it in more detail.) U.S. companies, with respect to much of their foreign source income (FSI), including that earned through their foreign subsidiaries, must (1) compute the portion that exceeds a 10% deemed return on tangible business assets held abroad, (2) include 50% of that amount in taxable income, and (3) pay U.S. tax on whatever liability remains after claiming foreign tax credits for 80% of the foreign taxes paid on that income.

Simplified illustration: say Acme Products has $100X of relevant FSI, and $100X of foreign business assets. A 10% return on the latter is $10X, so we reduce the relevant FSI by that amount, to $90X. Then we include half of it (or more specifically, include the whole thing then deduct half), reducing the net GILTI inclusion to $45X. At a 21% U.S. corporate tax rate, that would yield U.S. tax liability of $9.45X. But suppose the relevant foreign taxes paid on the FSI are $10X. 80% of that is $8X. So the U.S. tax liability on the GILTI inclusion is reduced from $9.45X to $1.45X.

Why foreign tax credits for only 80% of the foreign taxes paid? This reflects an issue that I think I can reasonably say I introduced to the literature, namely the incentive effects, from a unilateral national welfare standpoint, of having a 100% marginal reimbursement rate (MRR) for foreign taxes paid. Full foreign tax credits offer a 100% MRR. GILTI is a kind of global minimum tax rule at a 10.5% rate, but with full foreign tax credits U.S. companies with tax haven income might simply pay the full 10.5% abroad (perhaps economizing on the tax planning needed to stash it in pure havens) and we’d get zero revenue. There’s no direct gain to U.S. interests in this scenario from U.S. companies, to some extent owned by U.S. individuals, now paying higher foreign taxes and still no additional U.S. taxes.

The 80% foreign tax credit restores some incentive to economize on foreign taxes paid. It also kind of makes the GILTI a 13.125% global minimum tax. In theory, pay that rate globally and you’ll zero out your U.S. tax liability on GILTI. (But sometimes this is only true in theory, not in practice, due to various odd features of GILTI that can result, for example, in the loss of foreign tax credits due to a mismatch between when the taxable income arose under U.S. versus foreign law.)

This brings us to the treaty issue. Bilateral tax treaties between the U.S. and other countries generally say that one should offer either exemption or foreign tax credits for FSI of a resident of one of the treaty partners that was earned in the other treaty partner’s jurisdiction. So how can we both tax GILTI, to a degree, and offer only incomplete foreign tax credits?

I noted this issue in my work on foreign tax credits, but I think it’s fair to say that I expended close to zero intellectual capital in trying to resolve it. I left it for others to ponder, and happily they did. First Fadi Shaheen wrote on the issue, and now Mitchell Kane is following up. (Side point: it appears that the only thing they disagree about is whether they disagree about anything.)

Here is a very quick summary of Shaheen’s contribution: Both formally and in terms of the purpose of the foreign tax credit, it’s permissible to take a dollar of FSI and divide it into a portion that gets exemption and a portion that gets the foreign tax credit. A case in point is Option Z in international tax reform proposals that were disseminated a few years back by then-Chairman Baucus of the Senate Finance Committee. It provided that FSI would be 60% taxable and with full foreign tax credits allowed, and 40% exempt. Hence, if one put the two pieces back together, and given the then-prevailing 35% U.S. corporate tax rate, the covered FSI would in effect be taxed at 21 percent and would get 60% foreign tax credits.

Returning to Shaheen’s generalization, he argues, to my mind convincingly (on all grounds relevant to statutory interpretation) that, so long as the two pieces add up to at least 100%, a mixed approach is U.S. model treaty-compliant. (The case for its being OECD model treaty-compliant is apparently clearer still.) If that’s correct, then GILTI is more generous than it needs to be in order to satisfy tax treaties. Again, it taxes only 50% of the FSI (even ignoring exclusion of the deemed return on tangible business assets), yet offers 80% foreign tax credits.

Case closed if one accepts the analysis, except for one further issue. Treaties are bilateral, whereas GILTI applies globally. So, might it be an issue if Country A were to argue that less than 100% of the FSI that U.S. companies derived there was getting either exemption or foreign tax credits, given interactions with other FSI and foreign taxes within the GILTI basket? This is an issue that Kane and Shaheen both plan to consider further. (Shaheen’s article, like Kane’s draft, preceded GILTI.)

Even at this earlier stage, Kane offers a further development of Shaheen’s explication of how one can combine exemption with creditability without relying entirely either on one or on the other, so long as one provides sufficient relief under the two approaches considered jointly. I believe that his interpretation of what a typical bilateral tax treaty requires can be explained as follows:

(1) The residence country can’t cause its residents’ FSI to be taxed higher than domestic source income (considering both its and the source country’s taxes), unless this results from the source country’s imposing a higher tax;

(2) Where the above follows from the source country’s tax, the residence country can’t impose any residence-based tax on the FSI. But where the source country charges less tax on it than the residence country would if the income were earned in the residence country, the residence country can charge a tax equaling anything up to the amount of that shortfall. (Charging more would lead to violation of Rule 1 above.)

While this may initially sound both a bit abstract, and not especially close to the precise language of bilateral tax treaties addressing “double taxation,” Kane has done historical research showing how this relates to and fulfills the purposes expressed throughout the history of the treaty process regarding why double taxation is considered potentially bad and what the rules against it are trying to accomplish. So it is defensible based on underlying intention, as well as more formally via his analysis of typical treaty language.

Silverstein founded (in 1959!) the Tax Management Portfolio series of practitioner guidebooks, which is why I got the notification, as I was the author for the passive loss rules volume in that series (for which he recruited me when I had just left the Joint Committee on Taxation and was starting my academic career at the University of Chicago). He also successfully cajoled me to write a few very short practitioner pieces for a tax practitioners’ real estate journal as the passive loss regs started coming out.

Each only took me a few hours to write, but their publication led to an amusing episode that I’ve always remembered. A former fellow tax associate at my pre-Joint Committee law firm, who had preceded me into academics, came across these pieces, at a point when my first academic writings had not yet appeared in print (and of course there was no SSRN yet). He evidently concluded that this must be how I was directing my writing efforts as a legal academic, which would have been horrifyingly naive and misguided, as the University of Chicago Law School would have rated their value towards my earning tenure at zero. I ran into this individual at a conference, and while, he was trying to be gracious, his excruciating politeness about the pieces, along with an involuntary smile that he couldn’t quite suppress, brought to mind a man talking to one whose pants have fallen down and doesn’t realize it. But I figured there was no need to tell him what I was actually doing from an academic standpoint; he’d find out soon enough. (Yes, we’re in an ego-driven and competitive profession, and he was certainly no worse than anyone else, including me.)

Anyway, back to Leonard Silverstein. While the 1986 Act was in process, lobbyists who had technical issues to raise with staff would talk to us at the JCT. He was very good, in the sense that he understood our perspective as people who wanted the provisions we were working on to make consistent sense internally and be workable. E.g., I recall his deftness in saying that his client had asked him to raise two issues, one of which lacked merit but he had to mention it before we moved on, and the second more substantial. He was right about their relative merits, and I understood how he was working me but in a way that I had to appreciate. (Plus, the issue he raised truly was meritorious, in absolute terms whether or not comparatively so to the rest of the landscape, as the provision at issue, relating to the disallowance of miscellaneous itemized deductions, was a bit sketchy to begin with, in that it could result in overmeasuring net income.)

I subsequently heard from someone else that he referred to a couple of us at JCT, with whom he was discussing these issues, as “the kids on the Hill,” which I found amusing – I was in my late 20s – but by no means offensive. There was something a bit peculiar about an eminent senior law firm partner in his mid-60s, no doubt accustomed to deferential treatment most of the time, having to plead his case before a couple of bright-eyed recent law school grads who were excited about being near the pulse of what was happening at that moment. We certainly met plenty of senior law firm partners who were clueless about the sorts of arguments we’d respect, had never been contradicted by anyone for several decades, and thought they give us orders as if we were grocery store clerks. But he seemed to me to have a bemused and tolerant, albeit perhaps slightly weary, sense about the peculiarity of the status reversal implicit in his having to plead with us, at his career stage, to agree with him.

I thus got to like Silverstein, while not forgetting that he had his job to do and I had mine. Maybe it was mutual, as I’m sure we bantered a bit about the merits of the issues that he raised, I think with some shared enjoyment. When he found out that I was leaving JCT, he asked me if I wanted to join his firm, and when I said I was going to U Chicago he brought up the Tax Management Portfolio, which paid me enough to be worth my while at the time.

I don’t recall seeing him in person after I left Washington in 1987, although while I was still in Chicago (through 1995), we discussed TMP follow-ups by phone. But I’ve always remembered him fondly, and he somehow conveyed to me a sense of being a substantial person even though we never discussed anything that wasn’t narrowly professional.

The article’s current working title is “The New Non-Territorial U.S. International Tax System.” Final length may approach 30,000 words, although I feel that it moves fast through the issues that it covers, rather than lingering. It covers a great deal of ground, in part by reason of its joining together (1) a general normative discussion of how to best think about the main set of international income tax policy issues, and (2) a moderately detailed assessment of 3 key international provisions in the 2017 tax act: the BEAT, GILTI, and FDII.

Combining both of these parts in a single piece makes it a rather long haul. But I think this is the right design for the paper, as the two are interrelated. It’s hard to assess the new rules without a normative framework. And I think it’s worth my while to update the framework that I’ve set forth in previous work (such as my international tax book) given the changes since then in the legal environment.

I’ll be presenting the piece in Vienna and Oxford in June, Ann Arbor in October, and Copenhagen plus presumably NTA (in New Orleans) in November. My current publishing plan is to put it in Tax Notes, for rapid turnaround and broad professional readership. Given the piece’s length, it probably would need to appear in successive weeks as part 1 and part 2. Maybe, with luck, I can shoot for September publication. I’d then be able to post the article on SSRN once a few weeks have psssed (Tax Notes has rules about this).

In principle I suppose I should incorporate the ideas in the piece into a second edition of my international tax book, but I’m not sure if this will happen, as I might prefer to spend the time and effort working instead on my literature and high-end inequality book(s).