Time for more cat pandering

I wonder if one can tell just from these two pictures who is the calmer, and who the crazier, of these two brothers (whom I would presume are genetically just half-siblings). Whether or not the pictures give it away, it’s not a close call.

Here’s Gary:

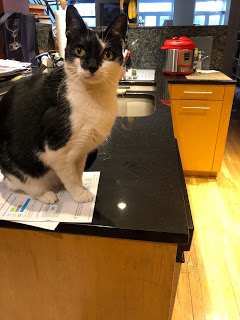

And here’s Sylvester:

So, whaddaya think?

NYU Tax Policy Colloquium, week 2: Rebecca Kysar’s Unraveling the Tax Treaty

NYU Tax Policy Colloquium, week 1: Stefanie Stancheva’s Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century

2019 NYU Tax Policy Colloquium

SCHEDULE FOR 2019 NYU TAX POLICY COLLOQUIUM

AALS Tax Section panel

We divided up in advance the particular topics to be discussed by each of us, and here is a very rough effort to reproduce in miniature my comments:

1) What have we learned in the past year about the economic impact of the 2017 tax act?

This morning, the Sun rose. Did we thereby learn something new about the Solar System? No, because that is exactly what we expected. By contrast, we most definitely would have learned something new (assuming we were still around to reflect about it) if, for some extraordinary reason, the Sun HADN’T risen in the morning today.

For exactly that reason, we haven’t learned all that much, in the past year, about the economic impact of the 2017 tax act. For example, there was absolutely no dispute, among serious, responsible, and knowledgeable people, that the act was going to lose a lot of revenue. And so it has – perhaps slightly on the high side, relative to “dynamic” expectations, but that is what I expected for various reasons.

We also “learned” that it did not stimulate a flood of new U.S. investment and other economic activity. But the only thing that was seriously in dispute in this dimension remains so – what might be the effects on U.S. investment over a much longer time horizon – given, e.g., that the relationship between statutory and effective tax rates for multinationals is not perfectly understood (and may have changed in multiple ways by reason of the 2017 act), and that the long-term effect of rising debt overhang will need more time to be observed.

There also seems to have been, unsurprisingly, a bit of mild Keynesian stimulus at the wrong time, i.e., when it was not really much needed. The rising debt overhang may make it harder in the future to use Keynesian stimulus through budget deficits at times when it might be far more needed.

Whether or not the flood of stock buybacks by U.S. companies was expected, it should have been. What else to do with the money that one is no longer constrained from “repatriating” as an accounting matter? And big U.S. companies with overseas profits were not generally cash-constrained with regard to U.S. investment.

The buybacks gave a great talking point to critics of the 2017 act, because their occurrence seemed so contradictory to the ridiculous talking points that were being made by the act’s proponents. But were the buybacks as such bad? Not really. They presumably shifted funds from companies that had no particular current use for the $$ to shareholders who now might find it transactionally cheaper to direct as they liked the value that was paid out. This can be a good thing. And if the funds transfer was merely being delayed under prior law by international deferral, that wasn’t really doing anyone any particular good (including the U.S. tax authorities).

2) International changes

I’ve discussed the 2017 U.S. international tax changes in greater detail on other occasions. But 3 points I made are as follows:

(a) In the aftermath of GILTI and the BEAT, it’s clearer than ever that we’re in a “post-territorial” world, i.e., one in which the old “worldwide versus territorial” debate has been shown to be orthogonal to the issues of main interest to policymakers.

(b) Many U.S. tax lawyers with whom I have spoken have an aesthetic dislike for the shift in U.S. international tax law, and not just because it wiped out much of their knowledge and allowed their junior associates to be on a more even knowledge footing with them, going forward. GILTI, the BEAT, and FDII (to the extent that anyone actually cares about it) have devalued legal advice based on judgment, relative to clients’ running lots of scenarios to guide tax planning.

E.g., suppose the client is wondering about whether it will face the BEAT this year, rather than escaping it under the so-called 3 percent rule (under which the BEAT doesn’t apply if less than 3% of one’s deductions are “base erosion tax benefits”). Even if one can set the numerator for this computation with certainty – which may not be the case – one is highly unlikely to know the denominator with anything close to certainty, as it may depend on the uncertain course of various business outcomes. So rather than just ask the lawyers what the BEAT means, firms may base key planning choices on running lots of probabilistic scenarios. Whether or not this is any worse than the prior state of the play ifor American or global welfare, it’s definitely much less fun for the tax lawyers.

(c) It’s been interesting to observe that a number of other countries appear to be intrigued by the idea of adopting their own versions of GILTI and the BEAT. While not a huge surprise, I didn’t regard this in advance as entirely certain..

3) Partial repeal of state and local tax (SALT) deductions

On this front, it’s been fun (if that’s the word for it) to observe the fault lines in academic debate between people who might typically agree more with each other than they do on this issue.

In the broader policymaking world, I’ve been at least mildly surprised by:

(a) the extent to which blue states have stepped forward to devise what might be called workarounds (I think this reflects the legislation’s nasty red state vs. blue state optics).

(b) the extent to which the Treasury, in response, has seemingly been willing to back away from past limited giveaways to what were mostly red state (albeit more limited) workaround schemes. I had wondered if the Treasury might either (i) feel more constrained by past rulings that favored, e.g., the use of state law tax credit tricks to make private school tuition effectively deductible, or (ii) be willing to respond with baldfaced inconsistency as between past red state and post-2017 blue state planning responses.

4) Where might we be headed next?

This remains unclear, given both the long-term fiscal gap and pervasive U.S. political uncertainty. But future action may need to focus more on new revenue sources (such as from VATs, including disguised versions such as the BAT/DBCFT, and/or from carbon taxes and the like), and less on “tax reform.”

Indeed, I think the term “tax reform” is now dead, other than as a synonym for “changes that I, the speaker, happen to like.” And good riddance, as it had outlived its usefulness.

From at least the 1950s through the 1970s, “tax reform” mainly meant broadening the base so that high-end effective rates would tend to come closer to matching the era’s steeply graduated statutory rates.

Then in the 1980s, “tax reform” came to mean broadening the base and lowering the rates, in a manner that was meant to be net revenue-neutral and distribution-neutral. It might also involve switching from the current income tax to a far more comprehensive version of the consumption tax, although that definition didn’t really get very far off the ground until more recent decades, when it continued to lack political traction.

After the so-called 2017 “tax reform” that lost immense revenue, was extremely regressive, and in many respects narrowed the tax base (e.g., via the egregious passthrough rules), I think we can forget about the term’s being used in public policymaking without evoking derisive laughter. Whether or not 1986 tax reform was tragedy (I don’t think it was), 2017 was definitely farce, and this implies no third act for the concept.

Close to publication

The article is now close to being published, as a chapter in the forthcoming Oxford University Press volume, Tax, Inequality, and Human Rights.

Tax issue re. Donald Trump, Michael Cohen, and Stormy Daniels

Reilly on Shaviro on the pass-through rules

He notes that I credit section 199A with having “achieved a rare and unenviable trifecta, by making the tax system less efficient, less fair, and more complicated,” and that I compare the 2017 proceedings to Gilded Age politics.

It’s a fun response by Reilly, and insofar as he disagrees with me it’s because my noting that the provision will require business people to “pay large sums to tax lawyers and accountants to figure out how best to structure their arrangements with an eye to minimizing federal tax liability” is good news for accountants such as him. “So a small portion of those large sums is coming my way.”

Reilly also quotes my noting, in the article, that the motivation for the pass-through rules appears to be sociological – aimed at rewarding members of the business elite while excluding member of the more educated professional and academic elites, simply because these are self-consciously distinct groups and the former were driving the bus in 2017.

He responds that this mistakenly classifies accountants as part of the educated classes and the intellectual elite. That may well be right, if one looks just as accountants from a sociological standpoint. But in the 199A list of professions banned from getting the 20% tax cut (other than below income phase-out), accountants were unlucky enough to get grouped, based on prior statutory precedents, with the likes of lawyers, doctors, and artists.

BTW, on a related note, I recently heard through the grapevine an explanation of why, at the last moment in the 2017 enactment process, architects and engineers were taken out of the professional classes’ exclusion from full pass-through benefits. The word is that Bechtel told their Congressional patrons (or servants?) to take out engineers, and architects got pulled too because the two groups were listed right next to each other, and a second deletion was thought useful in obscuring the political deal.

Gives you a nice sense of the sheer thoughtfulness behind contemporary Congressional Republican industrial policy.

Talks in Tel Aviv

Second, on Thursday, December 14, I’ll be among those discussing Tsilly Dagan’s excellent recent book, International Tax Policy: Between Competition and Cooperation. We international tax policy book authors need to stick together. Her book is complementary to mine, as I’m mainly interested in the unilateral angle (what a given country might want to do absent strategic interactions between countries) and she is more interested in the strategic aspect. In the time allotted to me, I’ll discuss underlying dilemmas in the field, the book’s main contributions, and follow-up qustions or issues.